Rio com Rodriguez.

I spent the summer of 2007 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, learning to speak Portuguese. After failing at Spanish, Japanese and Italian in school, this time I gave it a try in person. My impending college graduation depended on it. Sink or swim.

I knew little about Rio, nothing of Portuguese; I knew no one, arranged no language class and had no plans. I did have a few books, a “501” verbs book, a Portuguese-English dictionary and a Portuguese-English pocket dictionary. Also I carried a notebook in which to write down the new words I learned which no longer fit in the free space on my arm. (As it turns out, the back of your hand isn’t a bad place to write something that you want to remember.) I would figure it out along the way.

I spent a week or so living with a couch surfer, in a hostel, in a too smokey apartment that I found on Craigslist, and then back at the same hostel. I knew that none of these seemed like promising places for me to learn a new language; I was surrounded by the English speaking ‘round the world party tour.’

Through a new friend, I found a room for rent in a house in Santa Teresa. She had found a room but didn’t want to live with four men and a revolving cast of strange characters. None of them spoke English. I was barely able to convey that I wanted to rent the room. It was perfect.

I will be forever grateful for all the time, energy and patience with which my hosts treated me in the house in Santa Teresa. I would have been lucky to find such a nice place to stay; a house full of interesting and kind people who took me under their wings was miraculous. They taught me Portuguese. They would stop now and then when an important word came up that I should know. I would quickly scribble everything up and down my arms.

I learned to ask questions quickly and my always-obliging new friends made the rest easy and enjoyable. “Where is the bathroom?” and “my name is…” are classics, but I found the phrases “what is?” “How do you say?” and “how do you spell?” to be much more useful. Within a month I could converse with most, yet it was two weeks more before I could understand anything said by Rodriguez.

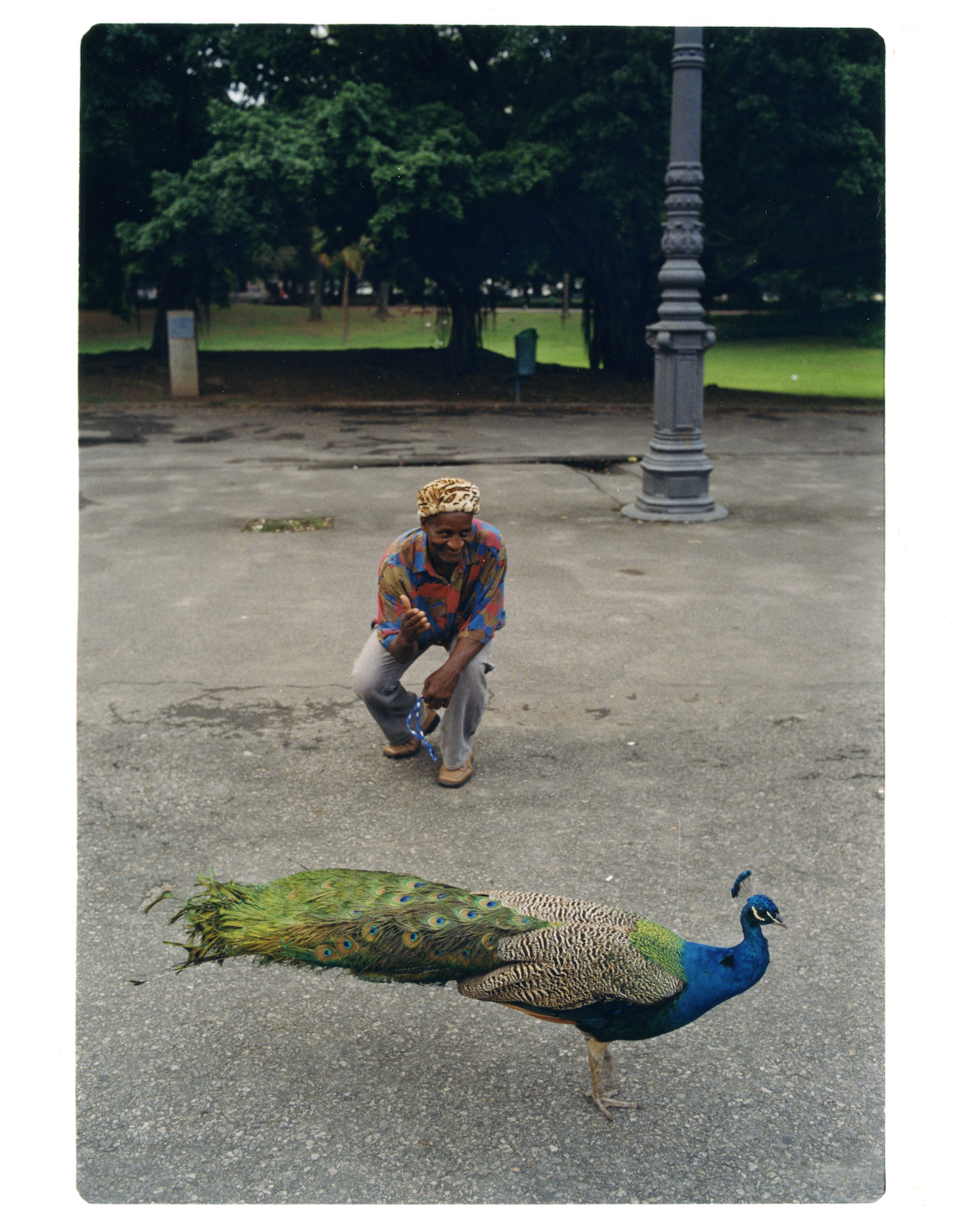

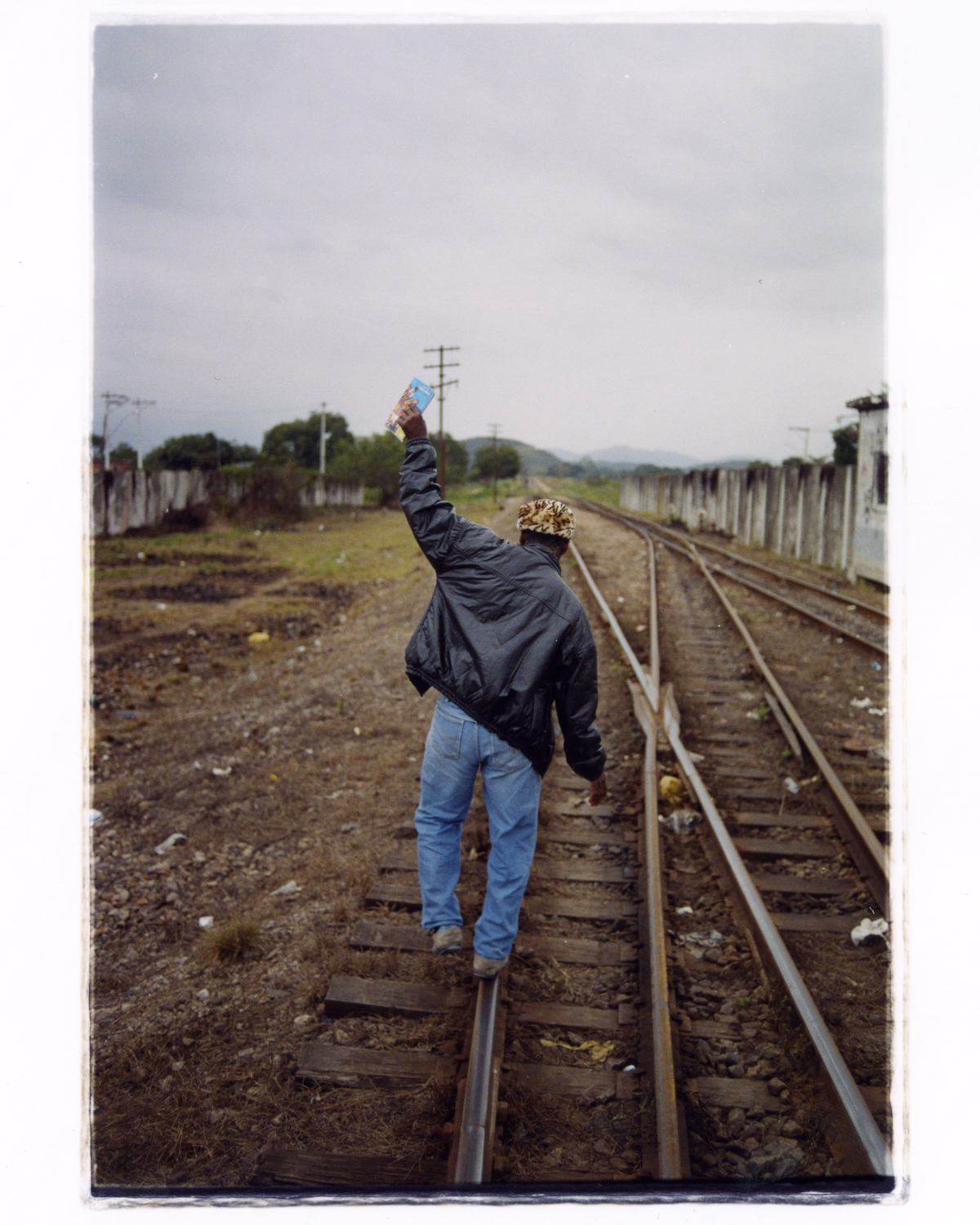

Most of these photos from my summer in rio are of Rodriguez and the things and places he showed me. While they are portraits of him, they are in a way a portrait of me. Of me learning Portuguese, little by little, of me exploring, goofing off, working, eating and resting, all with the man who lived in my garage.

The man who was a gold miner in Belem.

The man who was a pimp for the French foreign legion.

Who hocked junk on the streets.

Who flew to Amsterdam with shoes full of cocaine.

Who was a Macumba who practiced voodoo.

Who saw a wolfman and saw a man get devoured by a jaguar.

A man who loved to tell stories.

A man whose stories, for a long time at least, I couldn’t for the life of me understand.

This is what I know of Rio.

This is what I know of Rodriguez.

* * *

Marcus was an ex-motorcycle pilot who had once been a Coca-cola spokes-model, turned international playboy, turned south American bicycle adventurer, turned boarding house operator who dreamt of one day building a demoiselle, the first great airplane.(photo 7/60) He and his girlfriend Angela took me on educational trips and taught me much of the language. Sometimes it seemed that Marcus was really just speaking accented and disguised English. I could understand his clear and enunciated voice perfectly well before I could understand anyone else’s. Marcus rented rooms to a shifting cast of characters.

When I moved in, Chico and his Belgian girlfriend Christina , Roger and I rented rooms in the house. Rodriguez lived in the garage under our terrace, presumably rent free. I did not get to know Chico very well. He seemed set on a life far away in Belgium or Holland or England or from anywhere else that he could marry a Gringa tourist. Ticket to a better life.

Roger was in his thirties, working in Rio as a waiter and trying to start a career as a musician. He wanted to be a youtube superstar in the states, but he spoke no English.(6/60) While I’m sure he would have learned English, maybe singing is a little harder to pickup than English. It certainly is the case for me. His singing and guitar playing always amused me. Roger played to backup music for a troupe of clowns lead by his friend Pedrinho. They were something like street performers for children from what I could tell. In the picture of one of their shows (35/60) the adults seemed most interested in the super-chic and futuristic architecture of the new mall’s food court.

I spent much time with Rodriguez as neither one of us had anything to do all day, besides walk around the city. We were andarilhos; lovers of walking. Rodriguez seemed to trade some work around the house in exchange for his rent and maybe did a thing or two here and there, but mostly, at least for that summer, we were on vacation in Brazil.

Many of the next photographs are of Rodriguez telling me things before I could understand his words. Pictures 12 and 13/60 are of Rodriguez telling me about what people do outside our concrete wall, and about how uncivilized it was. Many of them are funny, at least I hope they are. While some would look up in a dictionary what they wanted to tell me, Rodriguez would show me.

* * *

* * *

Rodriguez showed me the beautiful views of Rio. We rode the Bonde, a rickety wooden trolley that still runs in Santa Teresa, as it once did all over the city (18/60). For about thirty cents you can buy a seat. Standing is free. While not notably fast, they don’t stop for anyone running and jumping aboard. The running board on which people stand is most definitely narrower than a size 13 shoe, which gets unsettling as the Bonde passes over an old aqueduct, standing room hanging over a drop of at least a hundred feet into moving traffic. There are nets, but I am convinced that they are more to stop loose change from cracking a windshield down below, than a falling passenger or fare collector; who climbs around the standing section using one hand for balance and one for bills and change.

* * *

Rodriguez showed me his own little plot of land, his Terreno in Niteroi, across the bay from Rio (31-33/60 ). Though tiny, he would raise okra there someday and already had a banana tree. He, like many others, had the mindset to own land, rather than rent, even in the middle or outskirts of a city. Informal land ownership in Rio and greater Brazil, on free land too steep for formal development, often starts out as a few people moving away to the ‘farm.’ Eventually it will grow into an overcrowded and urbanized favela like those closer to the city center. In Niteroi his friends call him Jimmy Cliff after the singer, for what reason I don’t know.

* * *

Rodriguez showed me his home town of Magé, where he was born, where his father had bought a piece of land that now has grown to an extended family complex. (37/60) I think the entire section of the town were Rodriguez’. I only heard his first name once, I think it was Valdemer. Everyone in Magé knew him as Apega Luz; Turned out light. A reference to his younger days when he used his extreme blackness to his advantage sneaking into nightclubs.

Magé is about thirty miles from Rio, at the end Baia de Guanabarra, the great stagnant bay that was once mistaken for a river, many Januaries ago. Rio de Janeiro and Niteroi flank the mouth of this great bay. There are 8 million people in Rio alone, not to mention Niteroi and the countless less dense settlements along the length of the bay. I was told forty percent of Rio is off of the main sewage grid, which means that the Baia de Guanabarra isn’t just filled with industrial pollutants. The smell was not pretty, yet people fished there all the time. I was told that the Japanese pay top dollar for shellfish from this spot. (39-42/60)

* * *

Questionable Delicious: Hot Dogs in Rio (23/60)

one hot dog bun

one hot dog

ketsup

mustard

mayo? special sauce

corn kernels

peas

potato chip sticks

a green olive

a pigeon egg?

Rodriguez would not eat them, citing some excuse like being too old. I love street food.

* * *

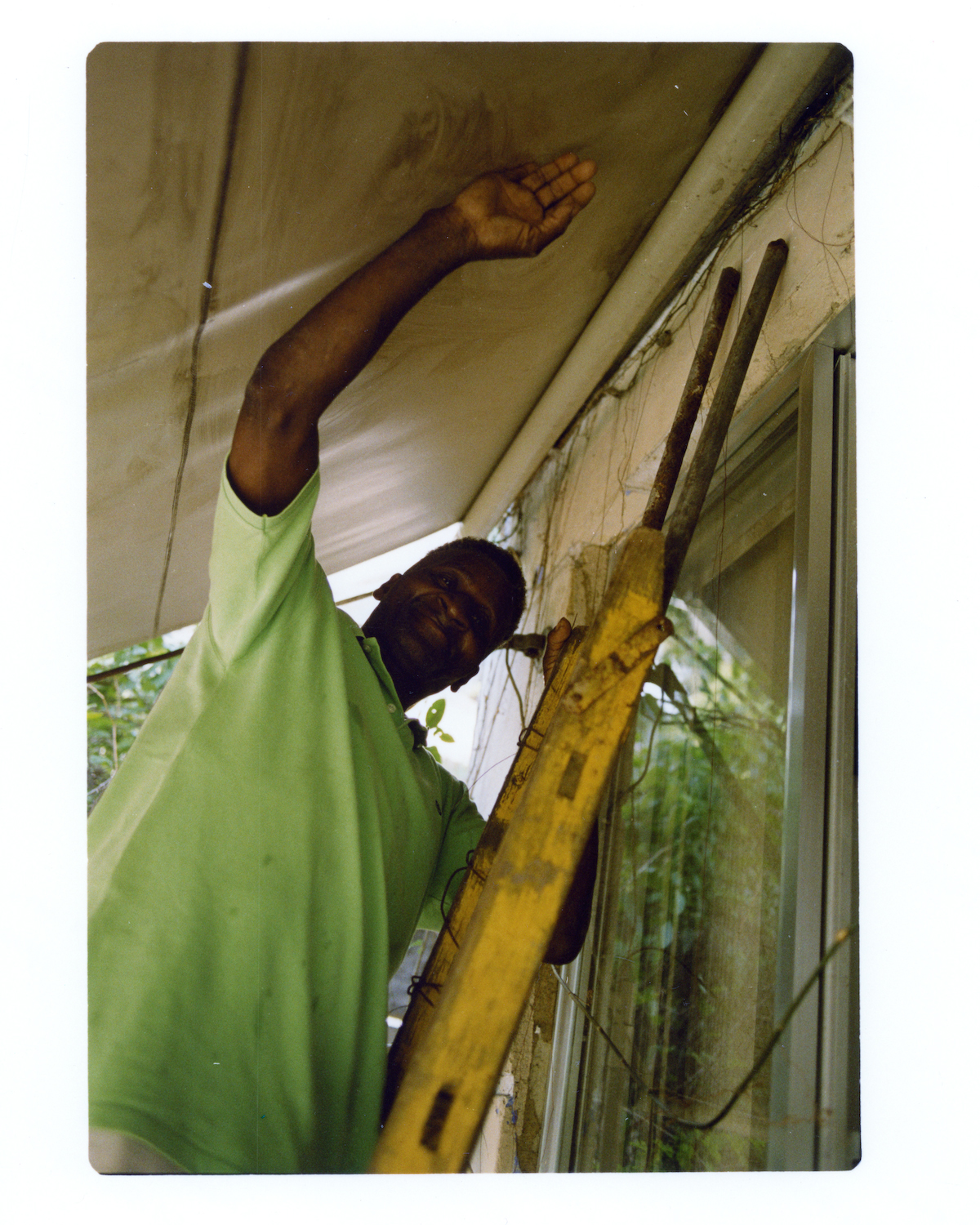

I once saw Rodriguez standing on a ladder, extended with two rusty old pipes, lashed on with twisted coat hangars. He was balanced above a giant glass window. (25/60) I tried to explain what a bad idea this was. My advice went unheeded, but I was taught a new word. Gambiarra: jerry rig. I called Rodriguez a Gambiarrador, someone who makes jerry rigs. Everyone laughed, and understood that while the suffix ‘–ador’ at the end of a noun means a person who makes that noun, Gambiarrador was not the right word for he who creates many contraptions out of only a pocket knife, coat hanger and some duct tape (‘silver tape’ said with an accent, in Portuguese). The word for someone with such truly Brazilian spirit is ‘um MacGyver.’

The contraption that dangled over my head and electrically heated my shower water in the morning resembled a toaster, and for that matter an electric chair after a little tinkering.

* * *

I had the honest pleasure of living with Tozão and his girlfriend Eilene, who had traded two months rent in the little room Rodriguez used to iron (29/60) in exchange for inking a tattoo on Marcus. Tozão and Eilene were traveling to the Amazon on a grand adventure, paying their way slowly by piercing and tattooing people in their mobile tattoo and body piercing van, in which they slept in while traveling. (44/60)

Rodriguez had no tattoos, only old bullet and knife scars.

* * *

There was a washing machine in the house, but Rodriguez and I washed our clothes by hand. I wonder why he still does this.

* * *

Drinking on the street is legal in Rio. You can, and I did, buy a bottle for cachaça wrapped in a bull’s foot with a shoulder strap and your favorite football logo on it. Mine being the estrella solitaria; the lone star of Botafogo (54/60). Rodriguez MacGyvered himself one out of what looked to me like a honey pot (45-46/60).

* * *

Rodriguez was an amazing drummer. He used to bang on anything he could find when he was a kid. Every part of his body gets involved in playing his drum set. The band that plays in Rodriguez’ loft in the garage got mad at me once for laughing at their lyrics to “zon’t let me down” by the Beatles. They didn’t care when I honestly told them that it was the best rendition that I had ever heard, just that the words were a little funny to me.

They were actually good enough to attract a few groupies, including ‘Polish Chicken Head,’ the balding man in the lower left throwing up a piece sign in photo 55/60 who presumably resembles this fleetingly feathered bird. I explained to them the more crass American interpretation of calling anyone a ‘Chickenhead.’

* * *

I once came home alone late to find a large man urinating on my front door. Scared, yet indignant, I yelled something like “Hey people live here!” To my surprise the man looked afraid of me in this deserted alleyway where ‘Death to America’’ was graffitied across the wall (14/60). Maybe he wasn’t afraid of me, but he was at least sorry. Maybe he didn’t think anyone lived there, or maybe he just didn’t think about it.

I didn’t believe many of Rodriguez’ earnest, yet dubious claims. I didn’t believe it when he mimed what went on in front of our house. I didn’t believe it when he told me about seeing the wolfman. Then again, I certainly wouldn’t have believed it if someone had told me about Rodriguez. Some things I guess you just have to show.

* * *